Your circadian rhythm is an internal 24-hour timing system that coordinates many biological processes. Think of it as the body’s master schedule: it helps decide when you feel awake, sleepy, hungry, energetic, or ready to digest and store food.

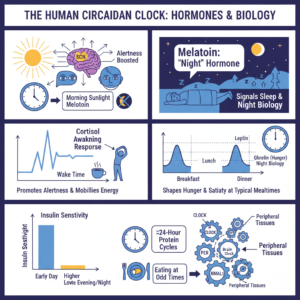

1) The Two Clocks

- The central clock (SCN) is the master clock in the brain that mainly responds to light and darkness through the eyes.

- Peripheral clocks are smaller clocks in organs like the liver, gut, pancreas, fat, and muscle that respond to meal timing, activity, and hormones.

- These clocks communicate so physiology stays coordinated: sleep, hormone release, body temperature, digestion, and metabolism follow daily rhythms.

2) Key Signals and Hormones

- Light activates the SCN and boosts alertness; morning sunlight sets “daytime,” suppressing melatonin.

- Melatonin is the “night” hormone produced in darkness that signals sleep onset and night time biology.

- Cortisol peaks near wake time (the cortisol awakening response) to promote alertness and mobilize energy.

- Ghrelin and leptin follow daily patterns, shaping hunger and satiety at typical mealtimes.

- Insulin sensitivity is generally higher earlier in the day and lower late evening and night, affecting carbohydrate handling.

- Clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY) create 24-hour protein cycles across tissues; eating at odd times can uncouple peripheral clocks from the brain clock.

3) Meal Timing, Digestion, and Metabolism

- Feeding strongly cues peripheral clocks, especially in the liver and digestive tract; regular mealtimes reinforce healthy rhythms.

- Morning meals are metabolically “cheaper,” with better insulin sensitivity and energy expenditure for handling glucose and fats.

- Late-night eating meets a body preparing for rest—digestion slows, insulin sensitivity drops, and post-meal blood sugar can rise, promoting fat storage and reflux.

- Frequent night time snacking signals “active/feeding,” disrupting the overnight fasting period used for repair and metabolic housekeeping.

4) Effects of Circadian Disruption

- Short-term effects include sleepiness, daytime fatigue, poor concentration, sluggish digestion, and mood swings.

- Chronic misalignment (shift work, persistent late nights, constant late eating) is linked with higher risks of weight gain, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, fatty liver and abnormal lipids, higher inflammation and cardiovascular risk, sleep disorders, poorer mental health, and gastrointestinal problems. These are associations but the links are strong.

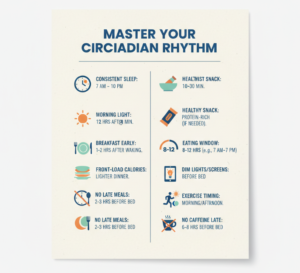

5) Practical, Evidence-Friendly Rules

- Wake and sleep at roughly the same times each day for consistency.

- Get 10–30 minutes of bright morning light; natural sunlight helps reset the master clock.

- Eat breakfast within 1–2 hours of waking to set peripheral clocks and leverage morning insulin sensitivity.

- Front-load calories earlier in the day and keep dinner lighter.

- Avoid heavy late meals; aim to finish eating 2–3 hours before bed.

- Limit late-night snacking; if needed, choose a small protein-rich option.

- Use a consistent 8–12 hour eating window (e.g., 7 am–7 pm) to preserve an overnight fast.

- Dim lights and reduce screens before bed; blue light suppresses melatonin.

- Time exercise for morning or afternoon; intense late-night workouts can delay sleep.

- Avoid caffeine late in the day; many do best stopping 6–8 hours before bedtime.

6) If You Can’t Keep a “Normal” Schedule

- Keep sleep routines as consistent as possible, even on days off.

- Use bright light strategically during shifts for alertness and blackout conditions for daytime sleep.

- When traveling, shift sleep and meal times ahead of the trip and use light exposure on arrival to adjust faster.

7) Short Sample Day

- 6:30 AM – Wake up → Step outside, get some sunlight, move a little.

- 7:00–8:00 AM – Breakfast → Focus on protein, healthy carbs, and fruit.

- 12:30–1:30 PM – Lunch → Build a balanced plate: protein, veggies, carbs, and healthy fats.

- 4:00–5:00 PM – Snack (optional) → Keep it light if you’re hungry.

- 7:00 PM – Dinner → Go for something lighter and easy to digest.

- Wrap up eating by 8:30 PM if bedtime is 10:30.

- 9:30 PM – Wind down → Dim the lights, unplug from screens, and relax.

8) Bottom Line

Your body runs on a daily schedule. Aligning sleep, light, activity, and meal timing with your internal clock supports better sleep, steadier energy, smoother digestion, and easier weight and blood sugar management. Right food at the right time means better metabolism and long-term health.