POST-PRANDIAL SOMNOLENCE

Postprandial somnolence—commonly known as a “food coma”—is the wave of drowsiness or fatigue that often follows a meal. While many people joke about “needing a nap after lunch,” this phenomenon is backed by real biology. It is the body’s way of shifting energy to focus on digestion, hormone balance, and metabolic processes.

Cultures around the world have long recognized the post-meal slump. In Spain and parts of Latin America, the siesta tradition allows a short nap after lunch. In Japan, “inemuri,” or dozing at work or school, is socially accepted, often after lunch breaks. Even in the U.S., Thanksgiving dinner has a reputation for leaving people sluggish. But what exactly causes this sleepiness, and why do certain meals make it worse?

The Science Behind Postprandial Somnolence

A. Blood Flow and Digestion

After eating, the body diverts blood to the digestive system to break down food. This can lead to a temporary reduction in blood flow to the brain, contributing to drowsiness.

The effect is subtle but noticeable. A light meal, like a salad or soup, may not trigger much drowsiness, but a heavy buffet or multi-course dinner requires far more digestive effort. That’s why people often feel the strongest food coma after indulgent meals.

B. Insulin, Glucose, and Hormones

When we eat carbohydrates, insulin levels rise to help regulate blood sugar. Insulin allows more tryptophan (an amino acid) to enter the brain, leading to increased serotonin and melatonin—which are associated with relaxation and sleep.

Here’s the chain reaction:

- Insulin spikes after a carb-heavy meal.

- More tryptophan (an amino acid) enters the brain.

- Tryptophan converts into serotonin, the “feel-good” neurotransmitter.

- Serotonin later converts into melatonin, the sleep hormone.

Together, serotonin and melatonin promote relaxation and drowsiness. This is why people often feel sleepy after a heavy meal.

Other hormones involved:

- Cholecystokinin (CCK): Released after eating, promotes digestion but also signals satiety and relaxation.

- Ghrelin: The hunger hormone decreases after eating, reducing alertness.

C. Circadian Rhythms & Afternoon Drowsiness

Our internal body clock, or circadian rhythm, naturally dips in the early afternoon—usually between 1 and 3 PM. If you wake up around 5 or 6 AM, this “afternoon slump” becomes more pronounced.

Add a meal on top of this natural dip, and the result is classic post-lunch drowsiness. That’s why offices often see lower productivity after lunch and why many cultures historically scheduled naps during this window.

The Role of Food Choices in Food Coma

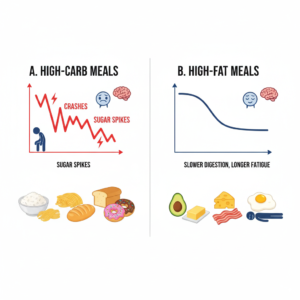

A. High-Carb Meals (Sugar Spikes and Crashes)

Refined carbohydrates—white rice, bread, pastries, and sweets—cause rapid spikes in blood sugar. After the spike, insulin quickly lowers glucose levels, leading to a “sugar crash” that intensifies fatigue.

Example: Eating a bowl of white pasta or rice or drinking soda or sweets at lunch may give you a short burst of energy, followed by heavy drowsiness an hour later. In contrast, whole grains and fiber-rich carbs release glucose more slowly, providing steadier energy.

B. High-Fat Meals (Slower Digestion, Longer Fatigue)

Fatty meals (fried foods, heavy meats, creamy dishes) take longer to digest, keeping the body focused on digestion longer, leading to prolonged tiredness. The digestive system stays active for hours, keeping blood flow concentrated in the gut. As a result, people often feel prolonged sluggishness after fast food or deep-fried snacks.

How to Minimize Postprandial Somnolence

A. Meal Composition & Portion Control

- Balance meals with fiber, protein, and healthy fats to prevent sugar spikes.

- Eat smaller, more frequent meals instead of large portions.

B. Timing & Activity

- Avoid eating large meals before important tasks (e.g., work meetings, driving).

- A short walk (5-10 minutes) after a meal helps to start the digestion process and keeps energy levels steady.

C. Hydration & Caffeine Considerations

- Dehydration can make post-meal fatigue worse.

- While coffee can help, consuming too much caffeine after a meal may cause an energy crash later.

D. Prioritize Night Sleep

- If you’re sleep-deprived the post-meal dip will be much worse.

E. Watch for Postprandial Hypotension

- Some older adults experience a fall in blood pressure after meals that causes marked lightheadedness/fatigue; medical review is important.

Possible Gut-Related Causes

- Delayed Gastric Emptying (Gastroparesis): Food stays longer in the stomach, causing bloating, fullness, and fatigue. This is commonly seen in diabetes, certain medications, or nerve-related gut dysfunction.

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): Excess bacteria in the small intestine can produce gas and toxins, leading to bloating, discomfort, and tiredness after meals.

- Malabsorption or Food Intolerances: Lactose intolerance, gluten sensitivity, or other malabsorption issues can trigger fatigue post meals. Undigested food may ferment, causing bloating and lethargy.

- Gut-Brain Axis Involvement: Gut irritation or inflammation can influence neurotransmitters (like serotonin), which affects energy and alertness leading to drowsiness.

Closing Thoughts

Postprandial somnolence—or food coma—is not a sign of weakness but a natural biological response. Blood flow shifts, hormonal changes, and circadian rhythms all contribute to the post-meal slump. The intensity depends largely on what and how much you eat.

By making smarter food choices—favoring balance over excess—and adopting lifestyle habits like hydration and light activity, you can minimize drowsiness while still enjoying satisfying meals. And in cultures that embrace naps, perhaps the food coma is not something to fight, but rather a reminder to listen to the body’s natural rhythms.

For further personalized guidance on balancing calories, nutrients, and long-term health, our team at Nutrition RX is here to help you every step of the way.